| 本文將說明美國與歐洲專寫附屬項的差異,如何把一個美國寫法的權利請求範圍,轉換成歐洲寫法的專利書請求項,而又不想會增加額外的費用?同時又可以重新定義發明,避免因多重附屬項而彰顯的單一性問題。 |

當我們在討論專利權範圍中的附屬項時,通常指的都是美國與歐洲撰寫方式上的差異,在這個方面,我們需要考慮三個主要議題,即成本、發明單一性以及增添的標的。

美國的制度是允許撰寫20個請求項,若超過20項則需要額外付費。這算是一個相當多的數量,能夠撰寫這麼多的請求項,是因為美國的專利制度使用一個簡單的依附系統。因為儘管是同一個發明概念,也有可能會產生不同層面的發明 (例如插頭跟插座) ,美國還允許最多三個獨立項以完善描述一個發明。多重附屬項在美國是准許的,不過多重附屬項只能允許附屬於單一的請求項,這也就是為什麼在撰寫美國專利權請求範圍時,會有很多的重複,每組附屬項通常會重複著與別組請求項相同的較佳實施例,而不管它們是依附在哪個獨立項。

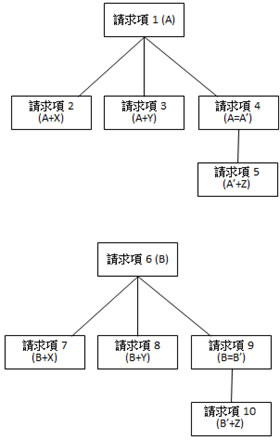

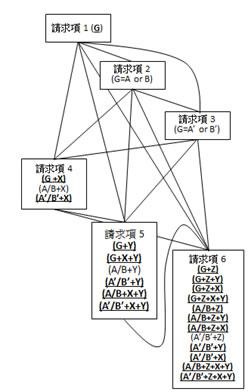

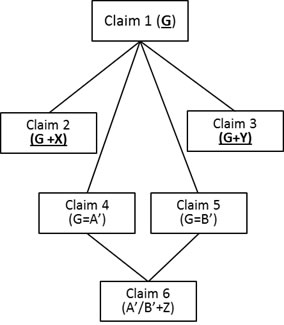

歐洲的撰寫方式主要使發明單一性的問題與附屬項更加聯繫在一起。在歐洲,超過15個請求項就必須額外付費。這是否意味著因為能撰寫的請求項較少,所以如果沒有多付超項費,能夠納入保護的較佳實施例也會較少呢?其實不盡然,因為多重附屬項是允許相同的請求項去依附,也就是包含發明的多個層面。關於這種現象請參考Box1,請注意請求項的數量是表達在樹狀圖中的第三排。

Box 1

|

美國寫法 – 10個請求項

|

歐洲寫法– 7個請求項

|

- 一產品A。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A包含有X。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A包含有Y。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A係為A’ 。

- 如請求項4所述之產品A,其中A’ 包含有Z。

- 一產品 B.

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B包含有X。

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B包含有Y。

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B為B’ 。

- 如請求項9所述之產品B,其中B’ 包含有Z。

|

- 一產品A。

- 一產品B。

- 如請求項1或2所述之產品A或B,其中A或B包含有X。

- 如請求項1或2所述之產品A或B,其中A或B包含有Y。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A系為A’。

- 如請求項2所述之產品B,其中B系為B’。

- 如請求項5或6所述之產品A或B,其中A或B包含有Z。

|

|

|

|

Box 1是一個非常簡單的轉換,從美國的寫法轉換成歐洲的寫法,其中只牽涉到簡單的多重附屬項而已。單單這樣,我們就可以把請求項的數量由10個減少到7個,然而如以下諸多理由所述,這仍不是具有效率的轉換方式。

多重附屬項意味著他們必須依附請求項1和請求項2,簡單的同時依附請求項1與請求項2,並無法真正改善這種狀況,因為附屬項仍須參照A或B,而因此表彰的問題是,這種寫法只是參照兩個分開的發明實體(A與B),而沒有定義他們為一個單獨的實體。

在這樣的狀況下,當任何審查委員收到這種說明書時,他們會質疑此案會有發明單一性的問題。當然,本案可能有一個很好的理由將該發明定義為兩個不同的實體,不過還是要看個案的具體狀況而定。從這個例子中,我們可以由歐洲實行多重附屬項的撰寫方式看出,這種寫法會警示我們申請案可能缺乏發明單一性的問題。

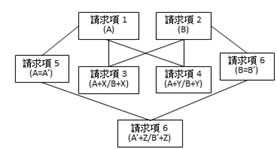

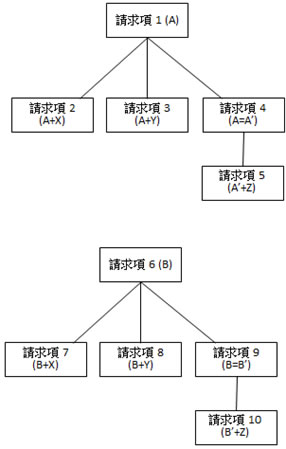

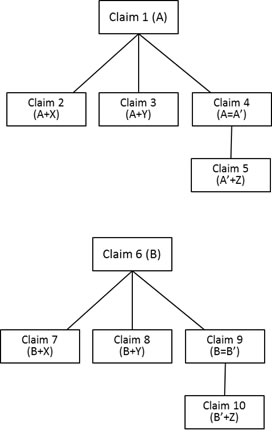

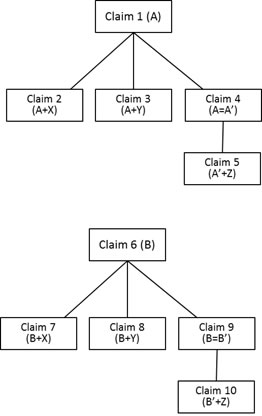

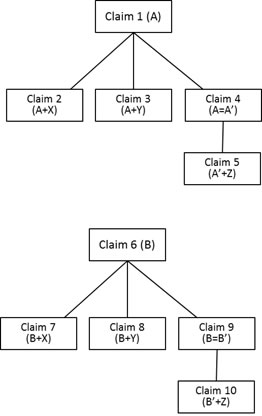

克服這個問題比較好的方法是將發明定義在一個單一的概念下,請參考Box 2,將A和B定義為一個統稱(上位概念)G,當加入這樣一個統稱G時,可能會伴隨專利標的之增加(如果不是,為何之前僅用了A與B呢?),至少在歐洲,這種做法會導致很仔細的審查,但很少會被核准。

Box 2

|

美國寫法 – 10個請求項

|

歐洲寫法– 6個請求項

|

- 一產品A。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A包含有X。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A包含有Y。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A係為A’ 。

- 如請求項4所述之產品A,其中A’ 包含有Z。

- 一產品 B.

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B包含有X。

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B包含有Y。

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B為B’ 。

- 如請求項9所述之產品B,其中B’ 包含有Z。

|

- 一產品 G。

- 如請求項1所述之產品G,其中G包含有X。

- 如請求項1或2所述之產品G,其中G包含有Y。

- 如請求項1-3所述之產品G,其中G係為A’。

- 如請求項1-3所述之產品G,其中G係為B’。

- 如請求項4或5所述之產品G,其中A’或B’ 包含有Z。

G是一個A和B的通稱。這種詞語通常牽涉到新增的標的,因此請求項中有新增的專利標的,將在下圖中用粗體與底線標示。

|

|

|

|

在此我們就發現了轉換到多重附屬項上的第二個問題:新增的標的。

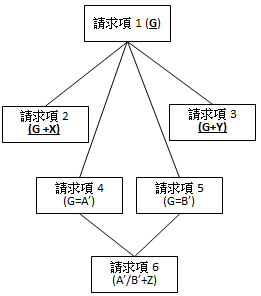

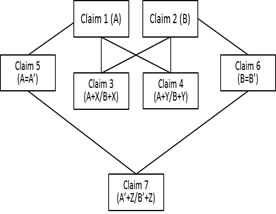

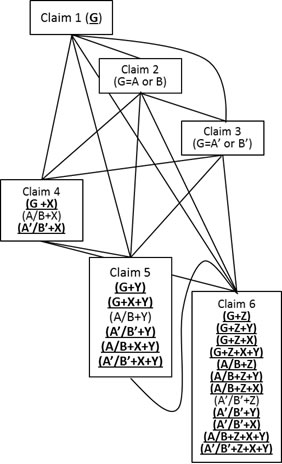

新增的標的可能會使多重附屬項非常有效,因為所有附屬項相對的特徵都能與其他的具有關聯,我們可以從Box 3看出這種關係。請注意,在Box 3中不同層面的發明被寫入多重附屬項中,而這是在美國寫法中不存在的版本,例如(A’ with Y and Z)或是(B and X and Y)。有趣的是,這樣用較少的請求項就可以搞定了!

這樣的結論似乎是不錯的。我們起因於想要減少請求項數量,進而避免增加成本,而這始終是一個目標(見Box 1),但這樣會造成單一性問題(可能是問題本來就存在)。再來,我們重新將發明定義在一個單一概念上(見Box 2),試圖改善這一點,通常會需要增加專利標的。既然要添加專利標的,不如藉由在更多的附屬項插入該等標的,以擴大範圍(見Box 3)。

Box 3

|

美國寫法 – 10個請求項

|

歐洲寫法– 6個請求項

|

- 一產品A。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A包含有X。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A包含有Y。

- 如請求項1所述之產品A,其中A係為A’ 。

- 如請求項4所述之產品A,其中A’ 包含有Z。

- 一產品 B。

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B包含有X。

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B包含有Y。

- 如請求項6所述之產品B,其中B為B’ 。

- 如請求項9所述之產品B,其中B’ 包含有Z。

|

- 一產品 G。

- 如請求項1所述之產品G,其中G係為A或B。

- 如請求項1或2所述之產品G,其中G係為A’或B’。

- 如請求項1-3 所述之產品G,其中G包含有X。

- 如請求項1-4 所述之產品G,其中G包含有Y。

- 如請求項1-5 所述之產品G,其中G包含有Z。

(下圖中所有使用粗體與底線標示的請求項,具有新增的專利標的)

|

|

|

|

上面的例子是要說明,如何把一個美國寫法的權利請求範圍,轉換成歐洲寫法的專利請求項,而又不會增加額外的費用。同時,我們又可以考慮重新定義發明,避免因多重附屬項而被彰顯的單一性問題。通常在做這些考慮時,可能係在有前案存在的前提下,而另一方面,這很可能意味需要增加專利標的,所以我們需要進行綜合評估。也就是說,這些請求項描述方式的轉換與各種考慮,我們若不是在優先權案的撰寫時(例如在其描述或說明書中),就是在提交國家階段申請的修改時,這兩個階段中來完成。第二個選項是比較不好的選擇,因為發生在優先權日與申請日之間的揭露可能會影響到請求項的有效性。因此,想要在之後節省請求項的超項費或是不被強迫分案,在不同國家申請時,提前規劃附屬項的安排就是很重要的功課,特別是在優先權案的撰寫階段。這就是為什麼在請求項的撰寫過程中,如本文所述之涉及各種層面的專業建議,是需要您所詳加考慮的。

| |

| 作者: | 郭史蒂夫 歐洲專利律師 |

| 現任: | 勁智財公司 Jinn IP, Ltd. www.jinnip.com |

| 經歷: | 北美智權教育訓練處 /歐洲專利律師

Bryers事務所 歐洲專利律師

Bugnion SpA事務所 歐洲專利學習律師

Notabartolo & Gervasi事務所 歐洲專利學習律師 歐洲專利局 實習生

英國牛津大學生物化學、細胞與分子生物系,生化碩士

英國倫敦大學瑪莉皇后學院,智財管理碩士 |

|

|

Claim dependencies and why they matter in US or Europe

Stefano John NAIP Education & Training Group / European Patent Attorney

When one discusses about claim dependencies in patent applications, one is mainly talking about the difference between the US system and the European model. Within this aspect, one has to consider about three major issues – costs, unity of invention and addition of subject matter.

The US system is thus structured to allow up to 20 claims to be examined without paying additional costs. This is quite a high number of claims and it results from the fact that the US system insists on simple dependency system. Because an invention may have different aspects to it even though they are still related to the same invention (for example a plug and socket invention), up to 3 independent claims are allowed to cover the separate aspects properly. Multiple dependent claims are allowed in the US system, but they are only allowed when they depend on single claims. This is why there is much repetition in the US claim system, each set of dependent claim typically repeating the same preferred embodiments as the other sets irrespective of the independent claim they depend on.

The European system uses mainly a system where the unity of invention is more associated with claim dependencies. In Europe, additional costs are incurred if there are more than 15 claims. Does this imposition for smaller number of claims mean that less preferred embodiments of the invention may not be allowed without spending more? Not really, because multiple dependencies allow one to cover more aspects of the invention in the same claim. See Box 1 as an example of this phenomenon. Please note that the number of claims is represented by the graphics tree in the third row of Box 1.

Box 1

|

US system – 10 claims

|

European system – 7 claims

|

- A product A.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is combined with X.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is combined with Y.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is A’.

- The product A according to claim 4, wherein A’ is combined with Z.

- A product B.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is combined with X.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is combined with Y.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is B’.

- The product B according to claim 9, wherein B’ is combined with Z.

|

- A product A.

- A product B.

- The product A or B according to claim 1 or 2, wherein A or B is combined with X.

- The product A or B according to claim 1 or 2, wherein A or B is combined with Y.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is A’.

- The product B according to claim 2, wherein B is B’.

- The product A or B according to claim 5 or 6, wherein A’ or B’ is combined with Z.

|

|

|

|

Box 1 is a very simple change from the US system to the European system that involves simply introducing multiple dependencies and nothing else. This achieves a reduction of the total number of claims from 10 to 7. It is however a less than efficient conversion for a couple of reasons which are intertwined.

The multiple dependencies system mean that they have to depend from both claim 1 and 2. Simply joining claim 1 and 2 together does not really improve the situation because the dependent claims would still refer to “A or B”. The problem is that the system highlights that one is trying to appropriate two separate entities of the invention (A and B) without ever defining them as a single entity.

In this respect, a question about unity of invention would arise which any Examiner would ask themselves when they receive an application. There may be a good reason for having the invention defined as two separate entities, but that would depend on the specific facts of the case. From this example, one can see that multiple dependencies according to how they are practiced in the European system lead one to highlight a possible lack of unity in the invention.

The best way to overcome this problem is by defining the invention in a single concept. See Box 2 for an illustration of this, where A and B have been amended by defining them with generic term G. But adding such a concept of G would nearly always be adding subject matter to an invention (if not, why use A and B?). In Europe, at least, such practices are scrutinised very specifically and rarely allowed.

Box 2

|

US system – 10 claims

|

European system – 6 claims

|

- A product A.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is combined with X.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is combined with Y.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is A’.

- The product A according to claim 4, wherein A’ is combined with Z.

- A product B.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is combined with X.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is combined with Y.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is B’.

- The product B according to claim 9, wherein B’ is combined with Z.

|

- A product G.

- The product G according to claim 1, wherein G is combined with X.

- The product G according to claim 1 or 2, wherein G is combined with Y.

- The product G according to any of claims 1-3, wherein G is A’.

- The product G according to claim 2, wherein G is B’.

- The product G according to claim 4 or 5, wherein A’ or B’ is combined with Z.

G is generic term for A and B. Such term often involves addition of subject matter and thus claims where there is added subject matter are highlighted below as bold and underlined

|

|

|

|

And herein we find the second issue of converting to multiple dependencies - addition of subject matter.

Adding subject matter may make the multiple dependencies very efficient because all the relative features of the dependent claims can be related to each other. This can be seen in Box 3. Please note how different aspects of the invention in Box 3 are claimed in multiple claims which do not exist in the US version, for example (A’ with Y and Z) or (B and X and Y). What is interesting is that this is all done with less number of claims!

Such a conclusion seems desirable. It starts with the necessity to reduce the number of claims to avoid costs, which is always desirable (see Box 1). That transition may highlight a problem regarding unity (which may exist anyway) - the redefining of the invention in a single invention (See Box2).

In attempting to sort that out, one has to often add subject matter. If you are adding subject matter, one might as well then improve one’s position by inserting additional subject matter through more dependencies (see Box 3).

Box 3

|

US system – 10 claims

|

European system – 6 claims

|

- A product A.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is combined with X.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is combined with Y.

- The product A according to claim 1, wherein A is A’.

- The product A according to claim 4, wherein A’ is combined with Z.

- A product B.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is combined with X.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is combined with Y.

- The product B according to claim 6, wherein B is B’.

- The product B according to claim 9, wherein B’ is combined with Z.

|

- A product G.

- The product G according to claim 1, wherein G is A or B.

- The product G according to claim 1 or 2, wherein G is A’ or B’.

- The product G according to any of claims 1-3, wherein G is combined with X.

- The product G according to any of claims 1-4, wherein G is combined with Y.

- The product G according to any of claims 1-5, wherein G is combined with Z.

(all claimed subject matter in bold and underlined is added subject matter)

|

|

|

|

The point of the above example is to illustrate what one has to consider when one wants to file a patent application from a US-style system to a European system and avoid unnecessary costs. On the one hand, one has to consider redefining one’s invention to avoid unity of invention issues which would be highlighted by a multiple dependency claim system. Such considerations probably involve assessing the invention in light of the prior art. On the other hand, it may mean adding subject matter. This means that consideration of such alternatives being described in the application can only be done at one of two stage – either during the drafting of the priority document (such as in the description/specification) or during the filing of the national application with an amended set of claims. The latter option is less desirable because any intervening disclosure between the priority and the filing may invalidate such claims. Hence, to save costs later on in excess claim fees or obligation to file divisional applications, it is important to plan ahead by taking into consideration claim dependencies for different countries as soon as possible, especially at the priority drafting stage. This is one reason why professional advice in juggling all these different aspects during the claim drafting is advised.

| |

| Author: | Stefano John, European Patent Attorney

JINN IP, LTD. www.jinnip.com |

| Experiences: | Patent Engineering Division Head, NAIPO

European Patent Attorney, Bryers

Trainee European Patent Attorney, Bugnion SpA

Trainee European Patent Attorney, Notabartolo & Gervasi

Internship, EPO |

|

|

|